Pricing

UCSD MGT 100 Week 6

How firms set prices

- Importance and challenge

- Common approaches

- Economic Value to the Customer

- Human factors

- Using Demand Model to Price

Pricing importance

#2 topic after two-sided value creation

Average US net margin is 8% (Damodaran Online)

Widely cited research by McKinsey

- 1% price increase can lead to 11% profit increase - 1% price decrease can lead to 8% profit decrease - Logic assumes no decrease in quantity - Correlations, but widely misinterpreted as causalConsultants say most companies price too low;

price is low-hanging fruit“Your margin is my opportunity”

Price changes are risky & scary

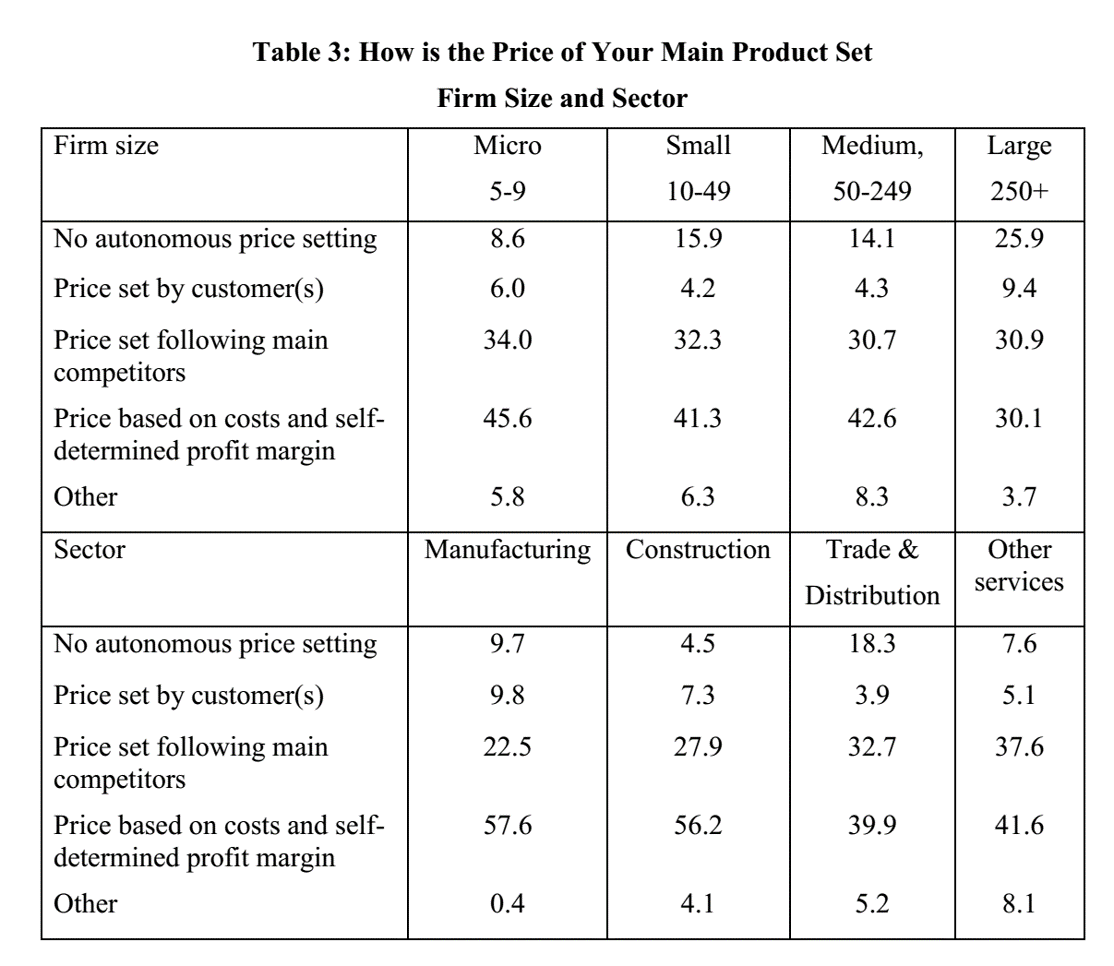

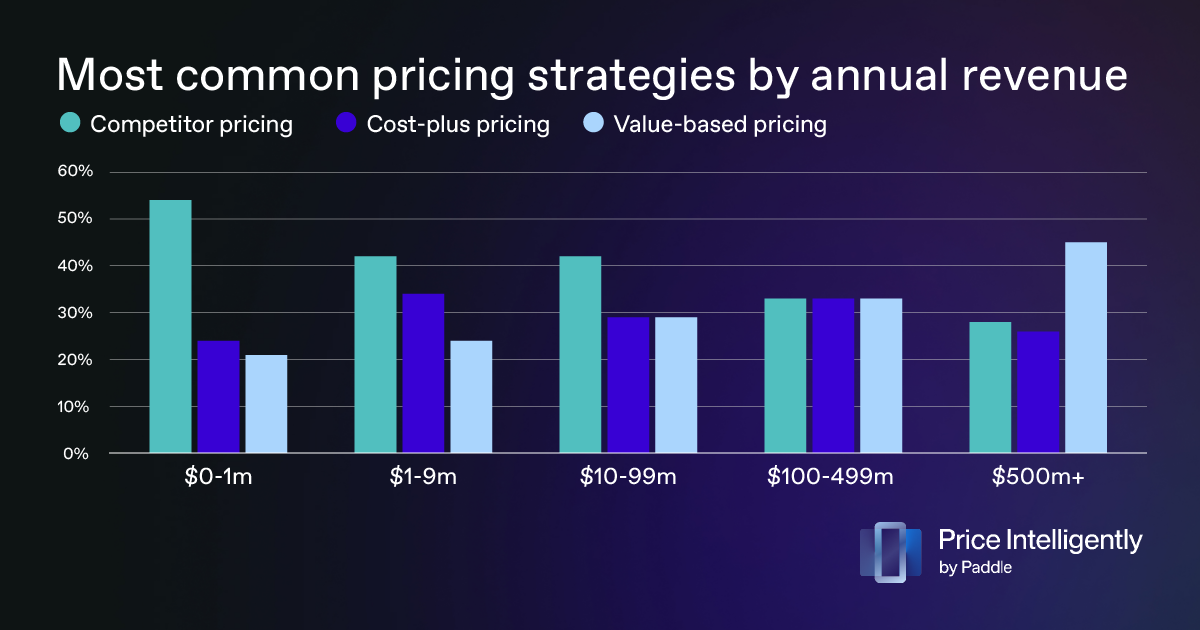

How firms set prices

Limited-data analyses

- EVC / Value pricing

- Competitor price benchmarking

- Cost-based pricing

Stated-Preference Data

- Open-ended: How much are you wtp? $___

- Prompted: Would you buy (product) at ($price)?

- Interviews, Focus Groups, Von Westendorp surveys

- Conjoint Analysis: Designs can be incentivized or not

Revealed-Preference Data

Simulated purchase environments, Test markets

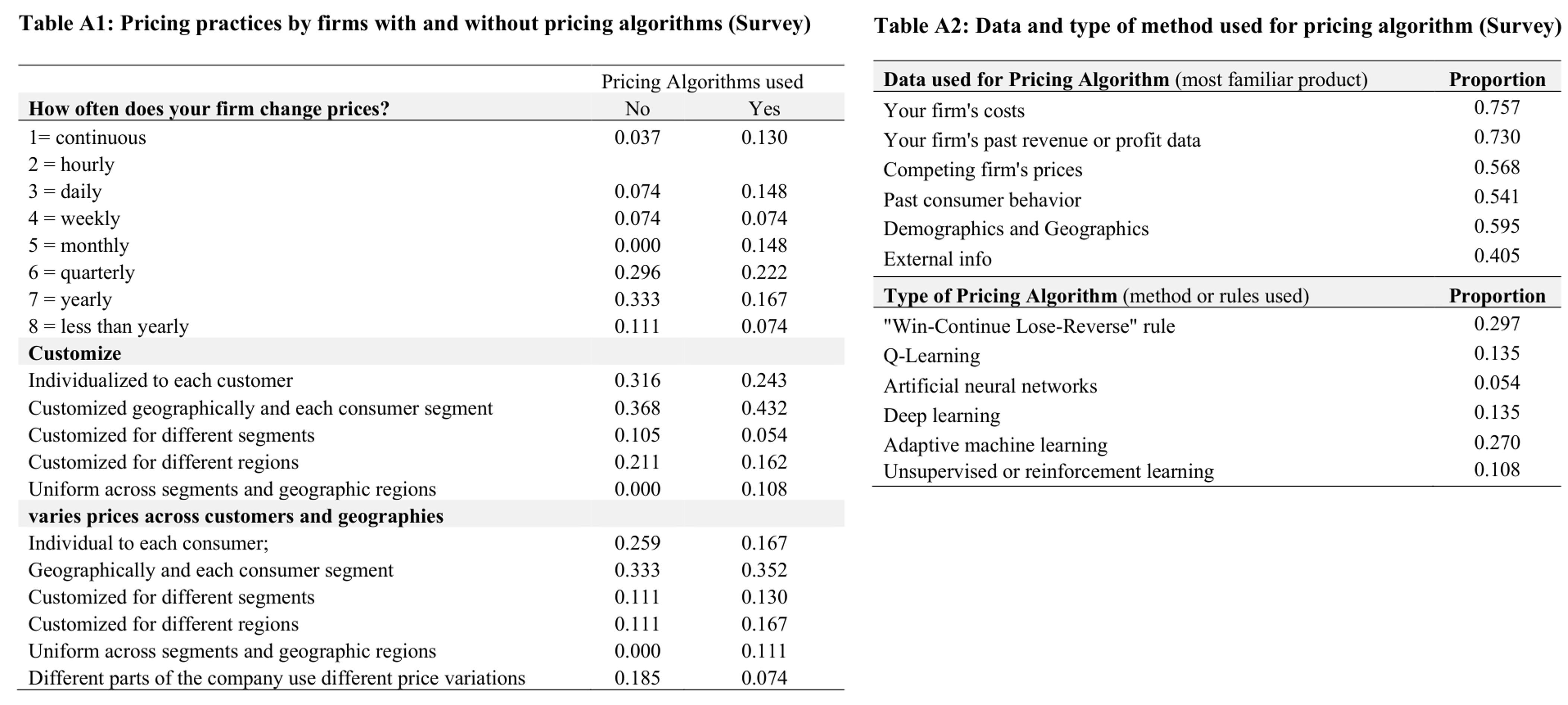

Algorithms (bandits, rev mgmt), Experiments (Amazon pricing labs)

Demand estimation

- Requires data, exogneous price variation, human attention/expertise

Customer co-determination

- Monopsony, auctions, negotiation, pay-what-you-want

None

- Seller takes market price

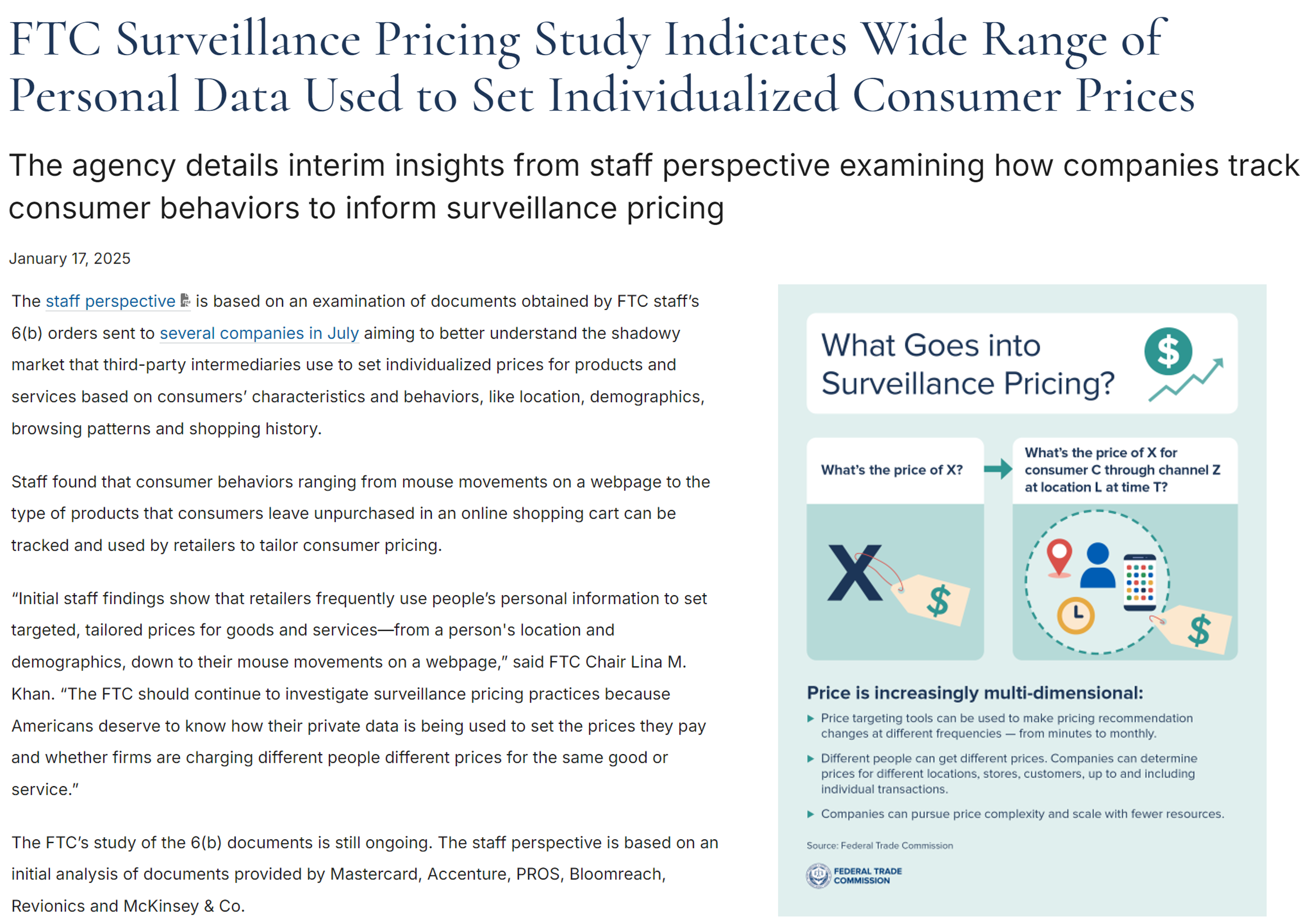

Pricing strategies are secret

What not announce your pricing strategy?

We can survey pricing managers anonymously, but (i) nonrandom selection, (ii) survey design inconsistencies, and (iii) self-reporting biases

Salt taken, let’s look at pricing manager surveys

Value Pricing: Price in (cost, wtp)

But… how do you learn wtp? Esp. if you have not sold before?

- For large time/budget: Conjoint, simulated purchase environments, test markets, …

- For small time/budget: Economic Value to the Customer (EVC)

EVC: estimates customer benefit from a product, relative to the next best alternative

EVC & VP are often used by new firms, highly differentiated products, firms lacking credible market research and related expertise

Steps: 1. Calculate EVC, 2. Choose a price in (Cost, EVC)

How to calculate EVC(x\(\vert\)y)

Select the best available alternative y and find its price

- Interview target customers to learn how they solve the core need (y) - If wrong y, EVC estimate will be too highDetermine non-price costs of using y and x

- Include start-up costs and/or post-purchase costs - Make sure NonPriceCosts(x) exclude the price of x (why?)Determine the incremental economic value of x over y

- Usually, functional benefits or non-price cost savingsEVC(x\(\vert\)y) = Price(y) + ( NonPriceCosts(x) - NonPriceCosts(y) ) + IncrementalValue(x\(\vert\)y)

- In practice, 99% of effort is getting the assumptions right

EVC tips

y might not be a commercial product.

EVC and y often vary across customer segments

- Calculate heterogeneous EVC(x|y) for multiple yUnquantifiable factors influence price selection in (cost,EVC)

If EVC(x\(\vert\)y)<0, reconsider product or target customer

Example: What is EVC(Batteriser\(\vert\)y)?

The Batteriser is a durable metal sleeve that increases disposable battery life by 800%. With a thickness of just 0.1 millimetres, the sleeve can be fitted over any size battery, in any size compartment

Assume the typical battery costs $0.50

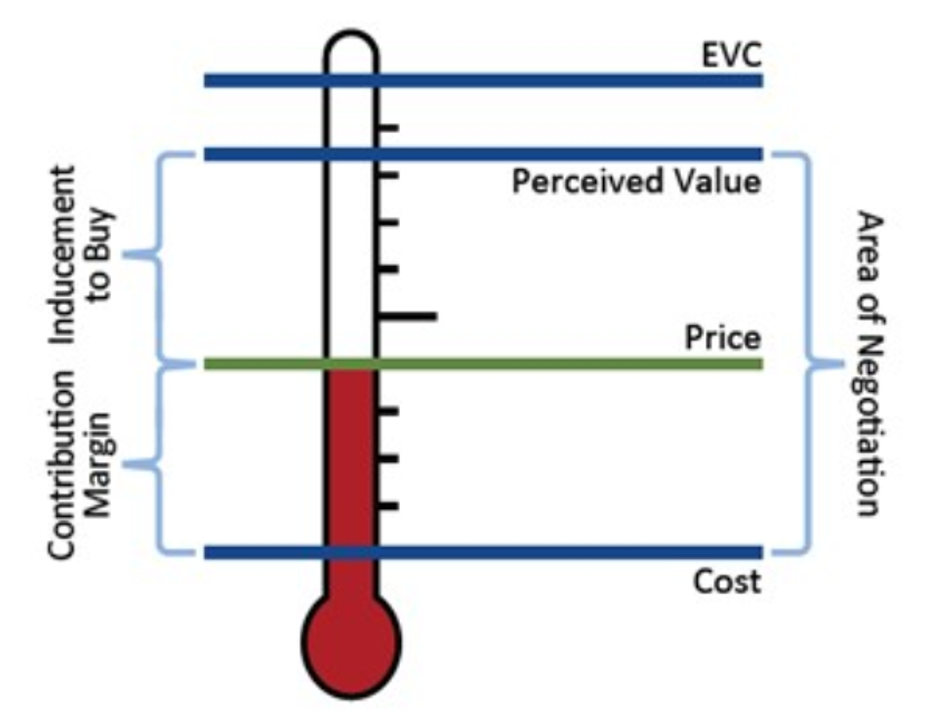

“Pricing Thermometer’’

How much inducement do you give your customer?

How will customers, competitors, suppliers react?

- SR vs. LR? More judgment than math. "Your margin is my opportunity"

Choosing p in (cost, EVC)

Some advise: \(Price = Cost + (EVC - Cost)*{z%}\)

- I've heard z = 25%, 33%, 50%, and 70% - Do you want profits or growth? What's your exit?Human factors to consider when making your judgment:

- Perceived benefit - actual benefit - Perceived costs - actual costs - Consumer price sensitivity, reference price of y - Established pricing benchmarks - Fairness, signaling - Customer risk of adoption, skepticism; brand credibility

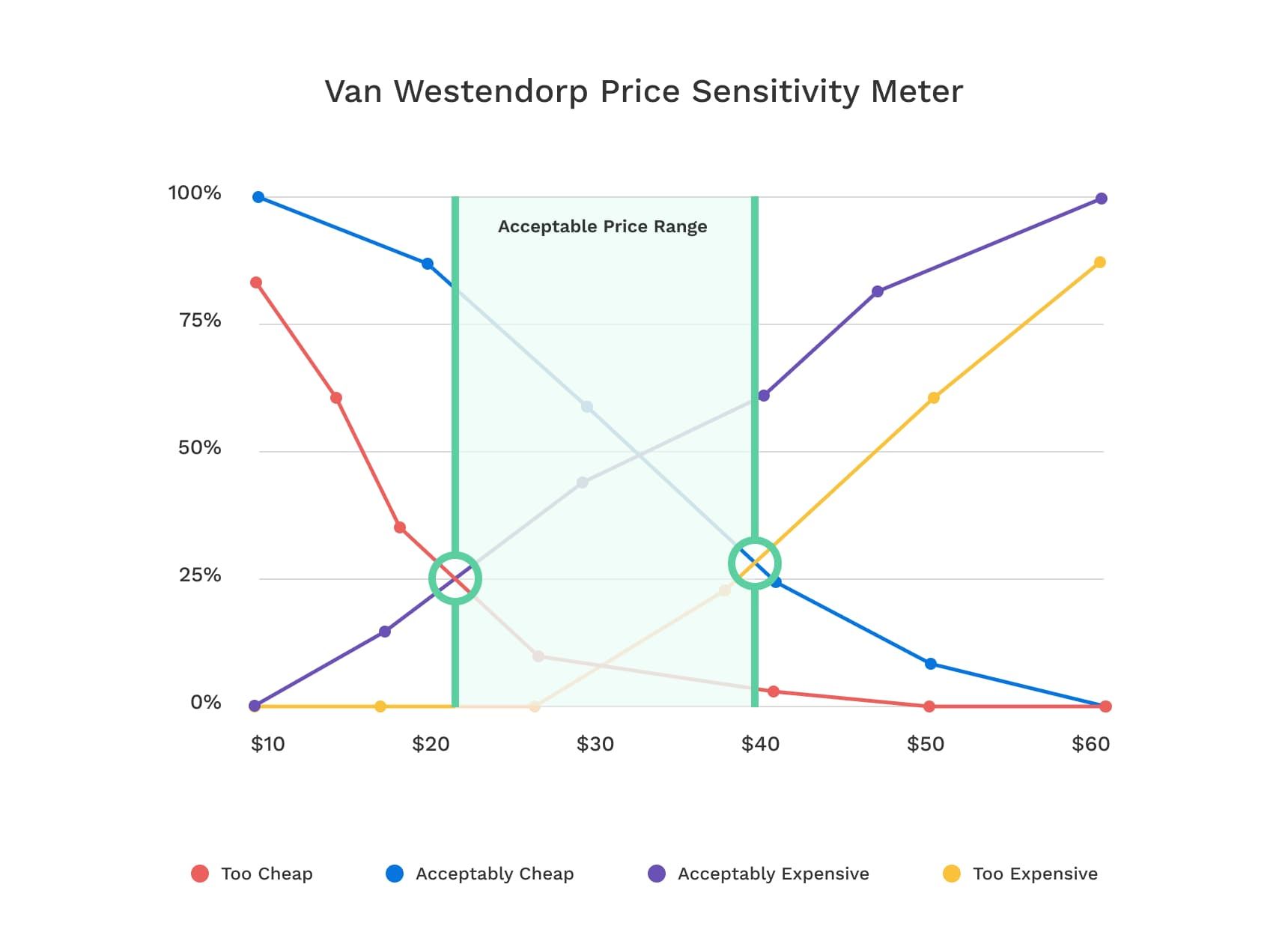

Van Westendorp Pricing Model

Goal: Estimate stated WTP range for each customer

Survey target customers: At price $X is (product)…

- Too Cheap? I.e., that you would question its quality - Acceptably Cheap? - Acceptably Expensive? - Too Expensive? I.e., that you would not consider buyingAsk for my values of $X, then plot 4 CDFs

- Too Cheap and Acceptably Cheap decrease with price - Acceptably Expensive and Too Expensive increase with price - Crossing points bound the Acceptable Price Range

“Too cheap” meets “Acceptably Expensive”: “Point of Marginal Cheapness”

- VW says: Price<PMC signals poor quality“Acceptably Cheap” meets “Too Expensive”: “Point of Marginal Expensiveness”

- VW says: Price>PME prices out most of your market“Too Cheap” meets “Too Expensive”: Min. # of price-refusers

“Good Value” meets “Expensive”: Possibly max. # of price-accepters

Strengths

- Estimable with survey data only; Estimates distributions of consumer heterogeneity; Incorporates reference prices and price-quality signals - Extensible to incorporate stated purchase intentions at each price. Add cost data, you can then max. profitsLimitations

- Identifies a price range, not a price - Thinking about 4 CDFs is difficult, easy to misinterpret - Stated-preference data only; disregards competitors & marginal costs, hence don't use standalone - Limited field evidence that it works well

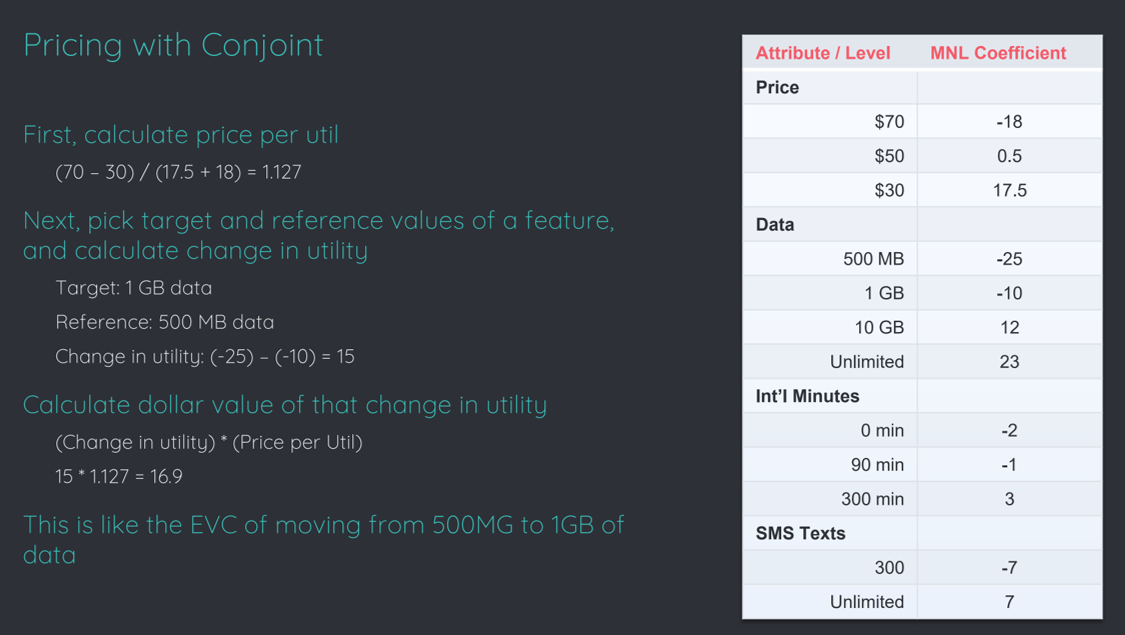

Conjoint works for pricing too

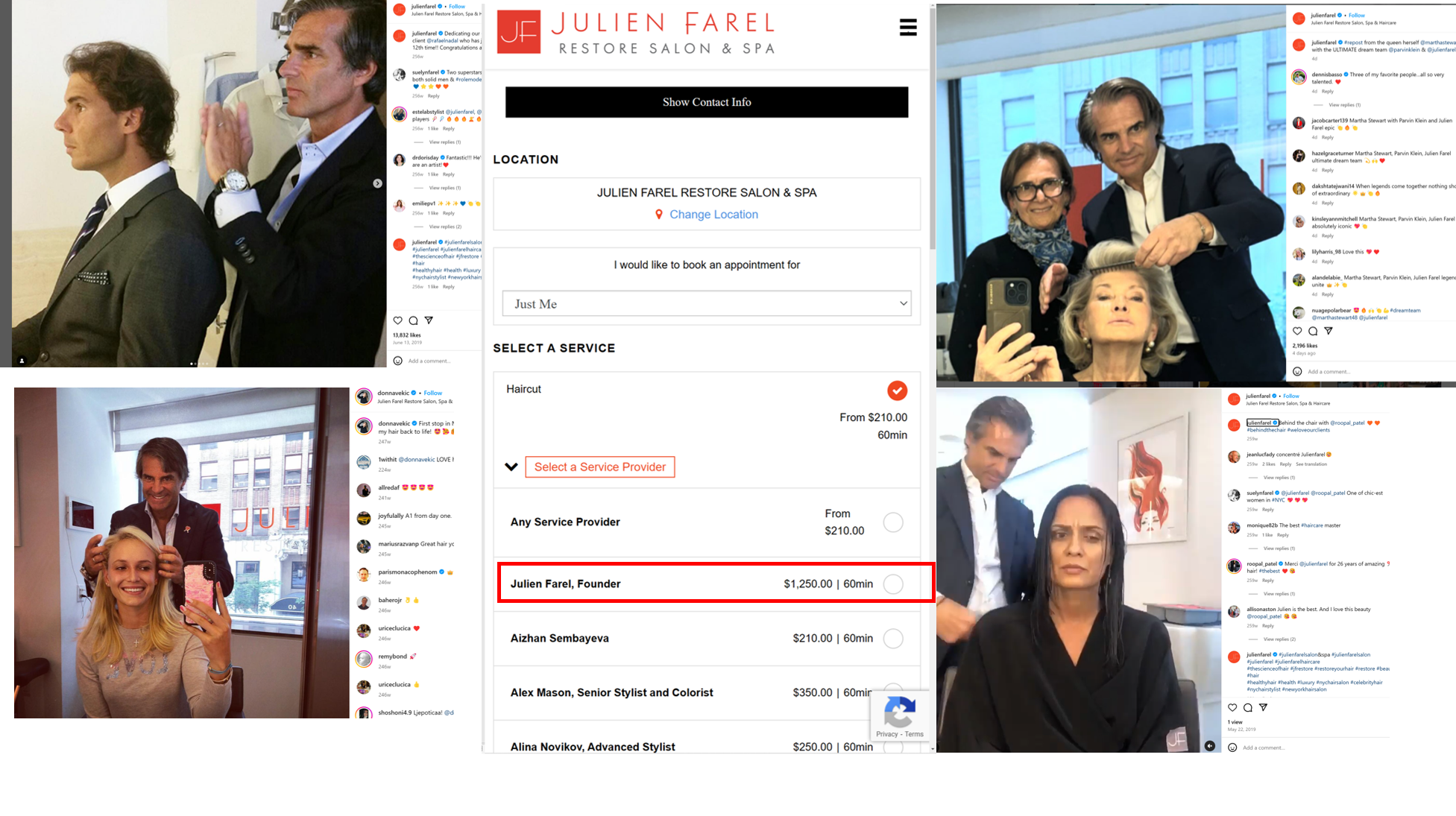

Signals and Perceived Quality

Signals of high quality

- High prices, Brand names, Warranties, Return policies, Ad spending - Costly signals when the firm doesn't deliver - Brand reputation can convey credibilitySignals of low quality

- Low prices, Price promotions, Price-matching guarantees - Signals that look too good to be true - "If it's so good, why is it so cheap?''Prescription: Price consistent with your quality position in the market

- Otherwise, you undercut your own message and leave money on the table - Findings replicate in numerous contexts

Human factors: Price as a signal

Human factors: Non-monetary costs

Total customer cost is

Cognitive cost to decide the purchase + Physical cost to acquire the product + Financial paymentSimplicity can increase sales. Remove frictions

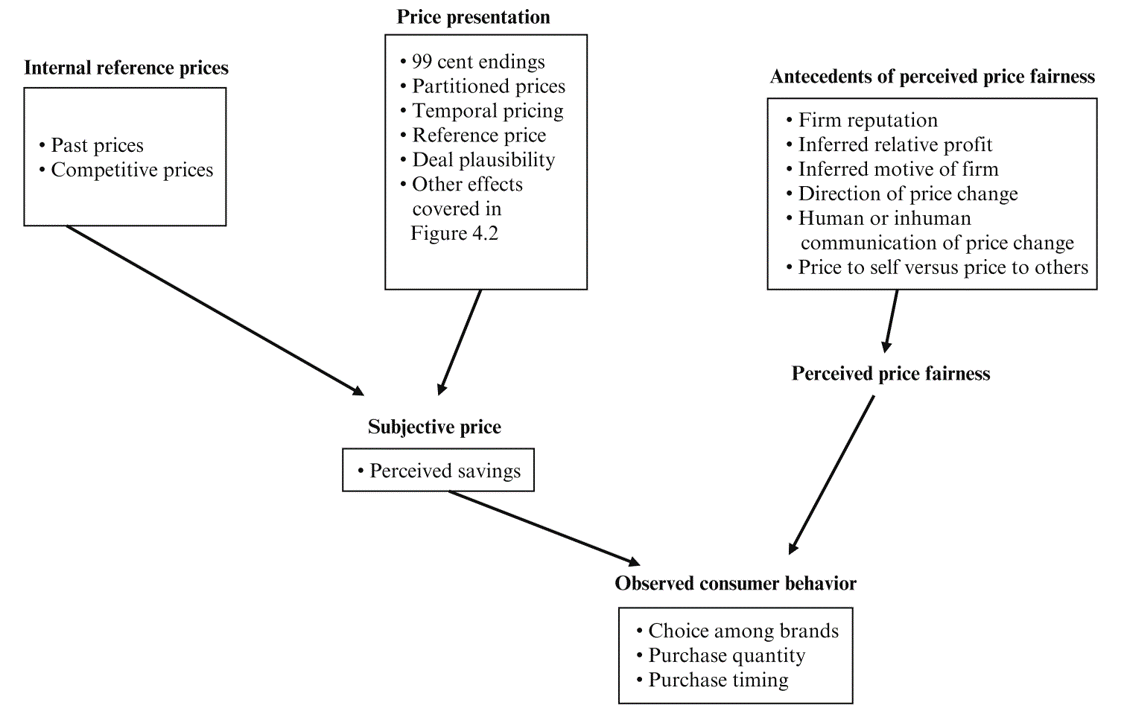

Human factors: Perceived prices

Which is the better bargain?

- Regular price $0.89, sale price $0.75

- Regular price $0.93, sale price $0.79

Left-digit bias: Demand Effects

Left-digit bias: Lyft rides

Human factors: Anchoring

- “You are lying on the beach on a hot lazy afternoon. For about an hour now, you have been thinking about an ice-cold bottle of your favorite beer. One of your friends gets up to make a phone call and offers to get you your favorite beer from a small run-down grocery store on the way back. Your friend says that the beer might be expensive and asks the maximum price that you are willing to pay. If the price is higher, your friend won’t buy the beer. What is your maximum price?

- … fancy resort hotel …

Human factors: Price salience

Show the price early, late or never?

- Drinks in a loud nightclub - USPS "Forever Stamps" - Price advertising, couponsPrice salience emphasizes Savings or Exclusivity

Human factors: Decoy effects

Choose 1:

- Brand A: Rated 50/100, priced at 1.80

- Brand B: Rated 70/100, priced at 2.60

33% chose A

Human factors: Decoy effects

Choose 1:

- Brand A: Rated 40/100, priced at 1.60

- Brand B: Rated 50/100, priced at 1.80

- Brand C: Rated 70/100, priced at 2.60

47% chose B (why?)

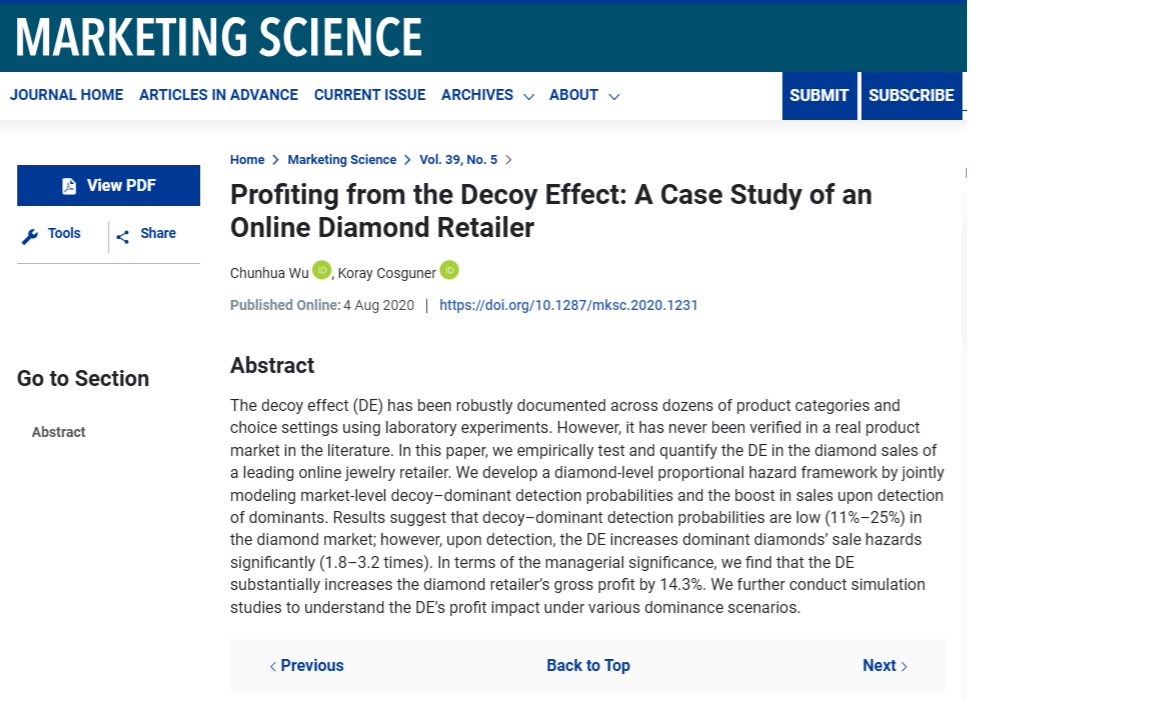

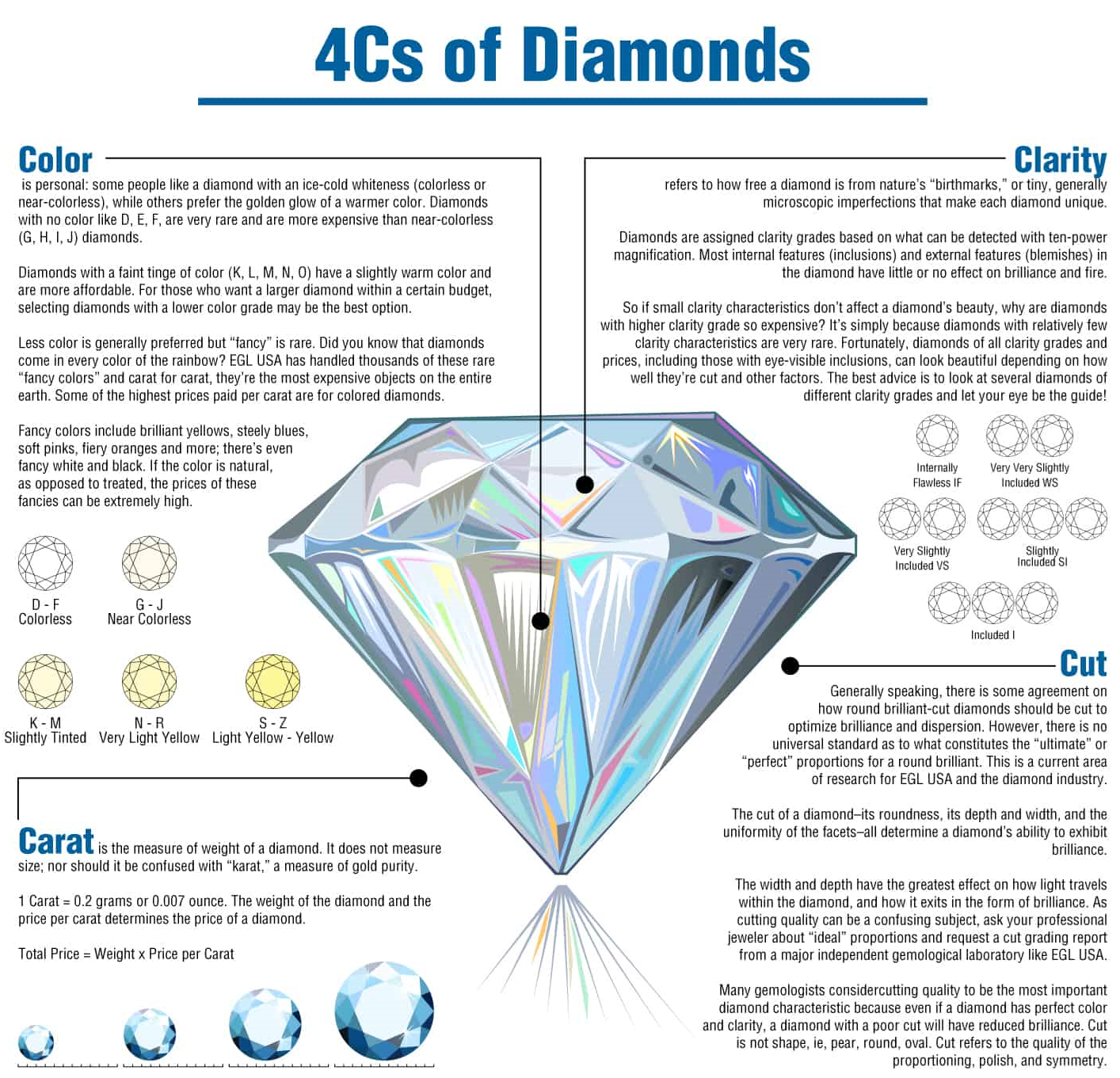

Field evidence in Diamonds

4 vertical attributes

Estimating Decoy Effects

Context: Online diamond sales

- #1 online diamond retailer, 50% share, big US brand - Retailer used a drop shipping model and fixed 18-20% markup - Anonymous diamond suppliers create listings, set prices - Diamonds listed individually; listings disappear upon purchase - Consumers filter by attributes and price - Retailer orders filtered listings by ascending price - Great setting: Rare-purchase category, high-price, limited/no fit attributes, many unknowledgeable consumersWu & Cosguner

- Scraped 7 months of 2.7 million daily diamond listings - Decoy-dominant relationships were frequent - Estimated decoy/dominant effect on time-to-sale

Dominant-Dominated Diamond Pair

- Dominant/decoy pair defined as either:

- Same attributes, different prices

- Dominated attributes, same price

- Dominated attributes, disordered prices

- Example:

- Dominant: 1-carat, Excellent cut, D color, VVS1 clarity, $3000 price

- Decoy: 1-carat, Very Good cut, D color, VVS1 clarity, $3000 price

- Authors observe listings by date and can estimate the listing ordering algorithm

- However, authors do not observe individual user search results, so findings estimate a model of how search results appeared to customers

Model estimates indicate

- 11%-25% of diamond listings had a dominant or decoy listing

- Dominant diamonds sold 1.8-3.2x faster with decoy listings

- Simulations predict Decoy Effect increased retailer’s gross profit by 14.3%

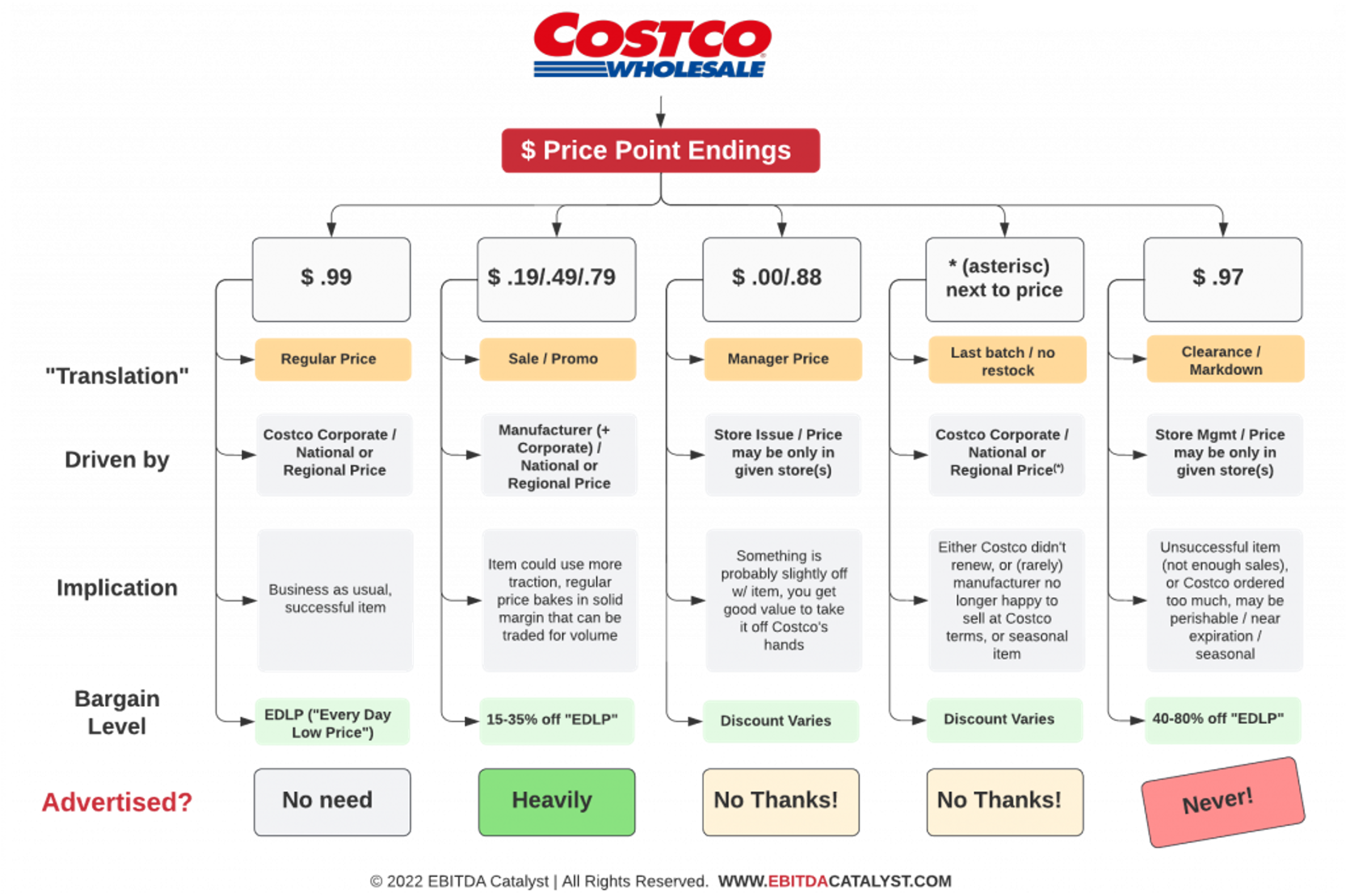

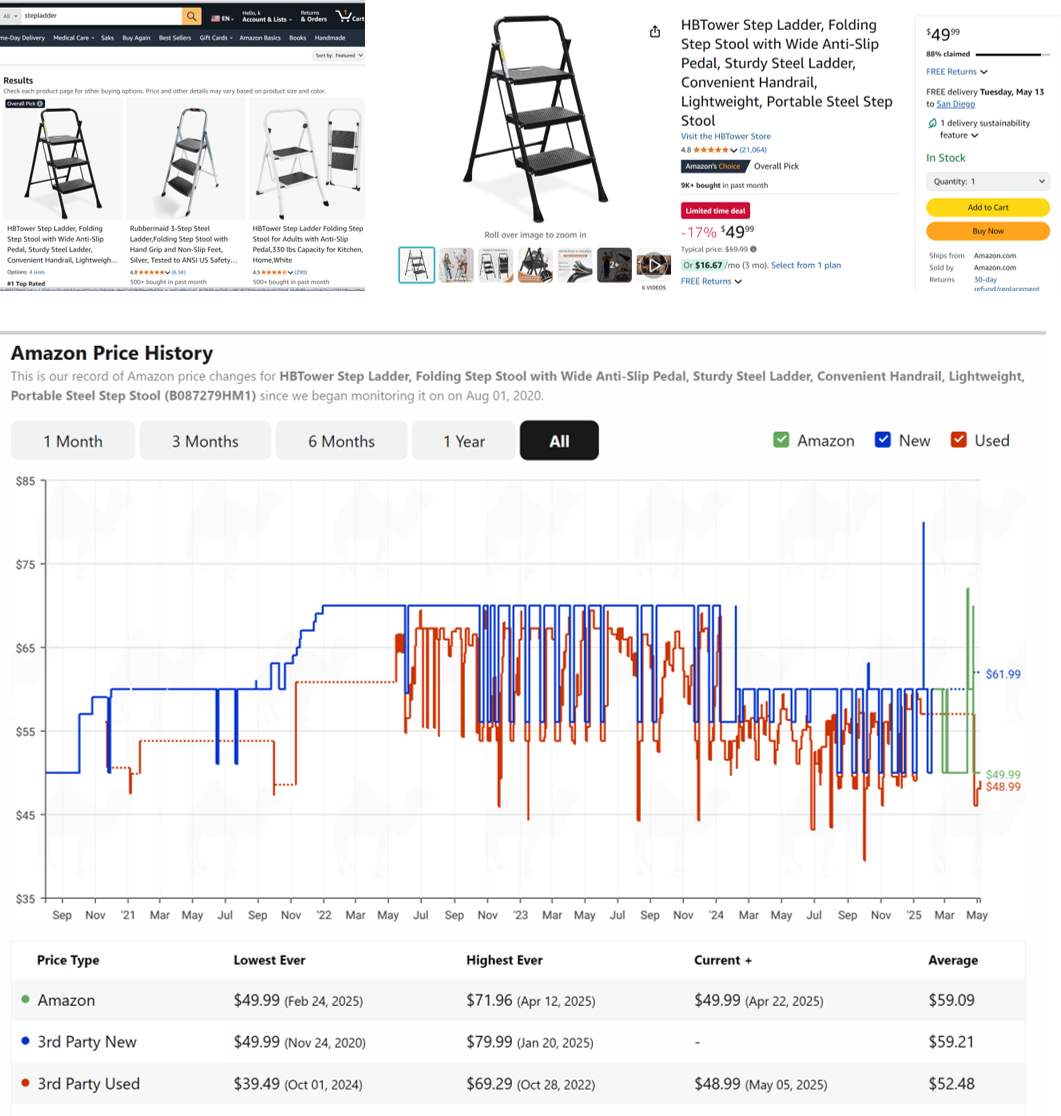

Economic factors: Price discrimination

Amazon v. B&N

Purchase time: Airline, Cruise tickets

Needs: e.g. Business vs. Home segments

Skimming by delivery time: Movie release windows

Geography: Typically accounts for 20% of variation in online prices

Quantity: Cups of coffee, Paper towels

Reduce resentment via new/loyal customer, merit (veterans, seniors), ability to pay/sliding scale, value provided, cost of supply

Always frame price differences as discounts

Economic factors: Beware a price war!

If you explicitly mention a competitor’s price

- You make Customer aware of Competitor

- Competitor will notice: You invite them to match or retaliate

Better to price-compare vs. unnamed/generic competitor

Who wins a price war?

- Only one winner: Customer

- All firms suffer, some die

- Most likely to survive: Seller with lowest cost structure

- Smart firms avoid price wars & keep costs secret

Price Elasticity of Demand

\(elas.=\frac{d(lnQ)}{d(lnP)}=\frac{P}{Q}\frac{dQ}{dP}\le 0\)

For \(-1<elas.<0\), we say demand is price-inelastic

For \(elas.<-1\), we say demand is price-elastic

Elasticity is “scale-free” : % change response to % change

We can calculate elasticity at a point, or on an interval

Results depend on interval width and demand curvatureNarrower intervals yield more precise elasticities

Price Elasticity of Demand

\(elas.=\frac{d(lnQ)}{d(lnP)}=\frac{P}{Q}\frac{dQ}{dP}\)

A special class of demand functions have constant elasticity

\(Q=e^a*P^b\) for \(a>0\) & \(b>0\), then \(elast.=b\)

Implies \(ln Q=\alpha+\beta lnP\), called “log-log”

Still need exogenous price variation for to estimate a causal effect Otherwise, beta should be interpreted as a correlationC.E. imposes a particular shape on demand & enables easy price optimization, given marginal cost data

But, C.E. restricts demand -> can lead to suboptimal pricing

How to use demand model to set price

\(q_j(p_j)=N\hat{s}_j(p_j)\)

Total contribution = \(\pi(p) = q_j(p_j)[p_j-c_j(q_j(p_j))]\)

Grid search:

- Choose candidate prices \(p_m = p_1, p_2, ..., p_M\)

- \(p^*=argmax_{p_m} \pi(p_m)\)

- Optional: Repeat using a more refined grid around \(p^*\)

We often assume \(c_j(q_j(p_j))=c\) for convenience

Multiproduct line pricing requires sum over brand’s owned products

Can you predict competitor price reaction, or how your demand responds to new competitor price? How?

Class script

Use demand model to trace out a demand curve

Compare different arc elasticity results

Conduct a grid search to find the profit-maximizing price, all else constant

Compare the grid search result to the CE-demand price

Consider multi-product price optimization

Recap

- The most common price setting methods are value pricing, competitor price matching, and cost-based pricing. All 3 are incomplete

- Consumers usually expect product prices to reflect quality positions in the marketplace

- Optimal pricing requires attention to both economic factors and human factors

Going further

Dynamic Online Pricing with Incomplete Information Using Multiarmed Bandit Experiments

Universal Paperclips : Fun price setting game